First published on Entrepreneur.com on 03.09.23

How Racism is Perpetuated within Social Media and Artificial Intelligence

Social technology and advertising giants celebrate heritage and history observances and make other public commitments to anti-racism, but I’ve seen first-hand just how performative all of this is at its core. The executive leaders of platforms like LinkedIn, Meta (Instagram) and ByteDance (TikTok) fail to uphold the anti-racist policies touted on their websites and in PR statements. Even artificial intelligence applications reflect the supremacist values of our society, especially in the United States.

Social media platforms prioritize whiteness

There’s a new movement that implores white women to do more to confront racism. Saira Rao, who is South Asian, and Regina Jackson, who is Black, are co-authors of a book on this topic, co-founders of Race2Dinner and have also co-produced the new documentary, “Deconstructing Karen.” Days after we connected on LinkedIn, Saira’s entire profile disappeared, as though she had never existed on the platform. Why would LinkedIn ban a New York Times bestselling author?

LinkedIn’s policy prohibits naming a group of people in posts (especially “white people” and “white women”), or using terms like racism or racist, among others. Saira posted about her book, “White Women,” but LinkedIn’s algorithm flagged it as a breach of policy in that her use of the phrase was considered a form of bullying and harassment.

This happens daily to creators of color, and it’s why you’ve likely seen many posts that use abbreviations like “yt women” or special characters to break up words like “rac.ism.” Ironically, the policy put in place to protect against hateful language is the very mechanism that gets Black, Brown, Indigenous and LGBTQIA+ creators regularly banned when they attempt to surface the racism, xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia and misogyny they experience.

Social media platforms seem to be institutions of the supremacy mindset that penalizes people of color who are vocal about racism and xenophobia. Speaking out about racism in the workplace typically equates to some level of retaliation, including being ghosted, demoted, left out of meetings and off email threads, or even terminated. The powers that be at LinkedIn, Meta, Twitter and TikTok do the same thing — in that they ban, shadowban or outright delete the accounts of Black and Brown creators.

Unlearning and dismantling racism requires that we talk about it openly in both public and private spaces. If social media corporations continue to penalize anyone who holds white men and women accountable for their racist commentary, how can we move toward belonging, equity and inclusion as a society?

Human issues with artificial intelligence

Social channels are not the only place where algorithmic technology both breeds and perpetuates racism. It happens on the results pages of every major search engine and within technology applications, both online and off.

My partner and I were at The Dali Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida, a few weeks ago. As part of a special exhibit called “The Shape of Dreams,” advertising agency Goodby Silverstein & Partners (GS&P) created “Dream Tapestry”, an interactive art installation powered by DALL-E — an artificial intelligence (AI) program that generates images using a dataset of text–image pairs from the internet in response to visitors’ descriptions of their dreams, called “prompts.” It’s a deep learning model using Google’s Imagen software and OpenAI, a start-up backed by Microsoft.

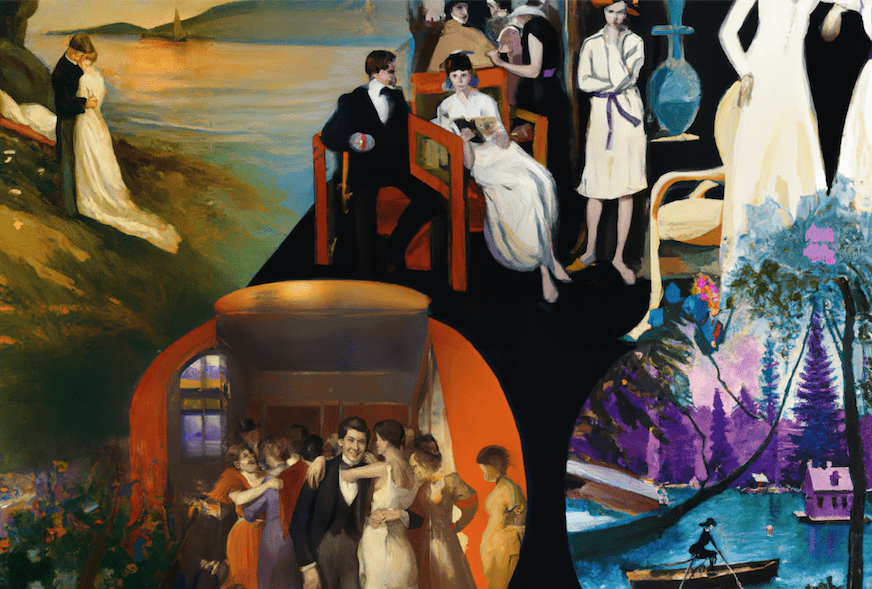

Since the installation accommodated only six people at a time, my partner and I, both white and queer, entered with two Black couples. Standing at individual kiosks, all six of us entered our dream descriptors. The AI digested our inputs and rendered images on the screens before us, pulling from Surrealist and Symbolistic images.

Then, the AI stitched together all six of our dream renderings on a giant board. We viewed the combination of our dreams as one cohesive work of art and downloaded our own rendering, as well as the tapestry of all six that the AI had generated. My partner and I left feeling that it was undoubtedly worth the length of time we stood in line.

On the flight back home, we reviewed her rendering, then mine. We were amazed by how similar they were despite the phrases we entered being so different. We then looked at the tapestry and noted that all four of the other renderings contained groups of colonials. None of the people in our group’s dreams were Black, meaning that the AI assumed that all subjects were white and/or its database contained no text-image pairs of Black people or from Black artists. Neither of us could know for sure, but we were willing to bet that our group wasn’t collectively dreaming of white men.

AI, like any other algorithm-based tech output, is only as accurate as its data input. Even with a high degree of granularity, the outputs default to categorizing “white as the norm.”

When most corporate leaders and application developers are cisgender, heterosexual, white men, the lens through which databases are created and filtered is, therefore, also cis/het/white. Therein lies the problem.

White leaders must expand their conscious awareness of the power they wield and the opportunity they have to right the wrongs of their past and present — starting with equal representation, listening to the lived experiences of people of the global majority (PGM), and getting comfortable with uncomfortable conversations.

You might ask, “Were there any Black Surrealist or Symbolic artists or images that depicted Black or Brown people during that era?” The answer is a resounding yes. Looking at the dream gallery online, an entire history seems to have been excluded from the database, imagery from African and African-Caribbean artists of the same era, categorized as Afro-Surrealism, as well as the Négritude movement in 1930’s France.

While the capability of DALL-E seems magical, I imagine we can do better than excluding Black and Brown artists and subjects. Through this exclusion, the AI shapes the narrative that we are collectively dreaming of a world solely comprised of white bodies.

When Jeff Goobdy, the cis/white co-founder and co-chairman of GS&P, talks about The Dream Tapestry, he refers to the power of the AI to reflect to us what we’re dreaming as a nation, or even globally, at this precise time in history. If the goal of DALL-E is to create a collective image of what we dream as a whole, it would seem that there’s an opportunity to depict the world that many of us want to live in, dream about living in — one that is diverse, equitable, inclusive and provides a sense of belonging for all genders and races.

Before LinkedIn bans another PGM and this installation makes its way into another museum, could we take an empathetic step back to understand how a lack of BIPOC representation reinforces a supremacy mindset and keeps us from truly seeing each other’s humanity?

About the author

Kelly Campbell is the founder of Consciousness Leaders and Trauma-Informed Conscious Leadership Coach to self-aware visionaries. She writes for Entrepreneur and has written for Forbes. They are the author of "Heal to Lead" (Wiley, 2024), a new book on transforming past trauma in order to uncover our innate leadership power.